-

Posts

1106 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Downloads

Recruiting - 2020

2019-2020 Football Season

Football

Entertainment

Sports

News and Business

Cloak Room

Transfer Portal

Recruiting

Events

Posts posted by We’reTexas

-

-

5 hours ago, Bozo_Casanova said:

Yup. I hate that branding, “moderate”. As if what we needed was compromise between competing elite factions instead of smashing them.

It stinks like fear and pee.

And while I like a lot about that book and what him and Derek Thompson are doing, San Francisco is just a terrible example, because it’s so sui generis. Every other big city with the same problems looks like it has shit together when you compare it to San Francisco- hell Ezra Klein praises Austin on housing, which is utter nonsense until the last 2 years. He’s just looking at MSA data, and what that is really telling him is not that Austin is doing a great job, but that it has sprawling suburbs in places where San Francisco has seawater.San Francisco is basically the same as LA and NYC in terms of housing and development, save for one regulatory quirk that allows it to claim the title NIMBY king. I think the main issue with Thompson and Klein’s writing over the past few years is that it is very relevant to the insular political discourse in those Blue coastal cities among your Blue coastal elites, but it’s not clear how their arguments apply to national politics.

They don’t seem to realize it, but the “Abundance” agenda is basically how growing Blue cities in flyover country have generally always operated (on a podcast with Matt Yglesias they used Houston as a red foil to San Francisco, which I found quite amusing). That’s great in one respect - I tell people all the time that San Francisco should be run like Houston. I loved Bill White! But that dude and everyone in his path continue to fail to win statewide office. I’m not really sure how their book will lead to any real impact.

-

2

2

-

-

5 minutes ago, Bozo_Casanova said:

Close but that’s not moderate. The moderate position is to placate progressive maxis with carveouts and set asides and limitations and covenants until they buy in, which makes the housing less abundant and solves less of the problem, which is a shortage of housing.

What you described as moderate is closer to the liberal position, which is: “we should allow the market to respond to the demand for housing. Fuck tankies and their bullshit. Their daddies pay their rent.”Fair, but in San Francisco (and I think LA and NYC?), the two wing of the party are literally called “moderates” and “progressives”, and you will see Ezra Klein et al use that terminology from time to time.

-

20 minutes ago, Valmy77 said:

Maybe, I couldn't really name what it is beyond just general grab bag of ideas that I think work.

I was just curious what you meant by that distinction.

I’m reading it as exemplified by the Blue state intra-Democratic party fight over housing, which has gotten quite heated since “Abundance” came out. Basically:

Moderates: We should build more housing, and in America we rely on private development for most housing, so we should facilitate that. Housing production has been stifled largely because of a regulatory framework enacted with progressive intentions but ultimately has resulted in a housing crisis, so we should consider removing these obstacles. We need to support realistic approaches towards housing affordability.

Progressives: No. Market-rate development enriches developers, and we hate developers. Removing regulations is deregulation, and that’s what Republicans do. Any new development should be public housing dedicated to working class people, and we should pay for by taxing the rich. We believe in unions, so these projects must be 100% union labor.

The former is objective-oriented and less concerned with getting tied up in ideological labels. The latter is driven by ideological allegiances and axiomatic beliefs - and totally unconcerned with actually delivering results. It’s also the wing of the party that has been steadily losing ground over the past five years

-

4

4

-

1

1

-

-

45 minutes ago, Valmy77 said:

As a Texan I am really jealous at how low those property taxes are.

$6,500 a year on a 1.5 million dollar house? What?

lol Prop 13 is wild.

-

1

1

-

-

I spend a good chunk of my life ranting about the unreasonableness of every aspect of California housing, but on a board of relatively affluent college graduates I will agree that it’s actually quite attainable. You will probably not get 3,000 square feet, but that’s a Texan mindset issue. You eventually get over it because you spend all your time outside!

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

1 hour ago, Foosters said:

Gonna throw this out there in case anyone is interested. Although I live in LA, I have some family in the Bay Area and find myself looking at housing in the region from time to time just to see what the market is like for future reference, should we decided to move up there once the kids are out of the house.

I see a lot of "well California is off the table due to housing costs," which I totally understand.

And yet, I continuously see home prices in Berkeley that defy explanation. I get that Berkeley is not for everyone, but I've always enjoyed it up there. Here's just a few homes that are currently on the market. Honestly, compared to prices in Austin, Dallas, and Houston, it doesn't seem THAT expensive. Obviously the PPSF is much higher. So perhaps, coming from Texas, it does seem exorbitant to pay over $1m for something under 2000 sqft. But man, these are some solid homes with beautiful views of the bay and the city. My wife claims that its because Berkeley is a bit out of the way from the Tech hubs, so it removes those folks from the market. Not sure if there's something to that. Maybe @We’reTexas can offer an explanation?

https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/1626-Le-Roy-Ave-Berkeley-CA-94709/24839512_zpid/

https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/981-Indian-Rock-Ave-Berkeley-CA-94707/24845573_zpid/

https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/851-Grizzly-Peak-Blvd-Berkeley-CA-94708/24848632_zpid/

https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/2314-Russell-St-Berkeley-CA-94705/24829827_zpid/

Looks like those are all listings in nice neighborhoods - sellers are shooting for around $1k per square foot these days. Which, to be fair, is a depressed price for the Bay due to lack of BART access and impossible commute to the Peninsula (also, the Berkeley Hills are in a high risk fire zone and going through the same insurance issues yall have unfortunately experienced).

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

-

2 hours ago, mdmost said:

Thanks for the update. I heard a segment on the Marketplace Morning Report on NPR a few weeks back about it being difficult to find contractors and builders. One of the hosts lost his house in the fire. The thought was most of the builders would be heading to Palisades first given the price tag of those homes and the money in that area. You just don't hear much now from the media about how things are going in the aftermath.

I imagine a huge chunk of longtime Palisades residents can’t afford to rebuild and the County has totally fucked things up by only trying to fast-lane like for like rebuilds. Ugly backlash of 50 years of Prop 13 and NIMBYISM.

-

-

18 hours ago, MrX said:

Don’t sleep on the Delaware coast

I definitely have after enough Orange Crushes at Dewey Beach.

-

22 minutes ago, David Dennison said:

I thought Gavin Newsom wanted to be president.

I guess not.

Hey, at least he went from Steve Bannon to jumping on the Abundance bandwagon.

-

1 hour ago, Im_smarter_then_you said:

Yea. Lots of NIMBYs who pretend to be environmentalist types out here.

FIFY

-

I don’t think it ever was.

-

1

1

-

-

53 minutes ago, tbone_ said:

That’s because people in the policy space don’t know shit. Allowing more density will help, sort of. But it won’t be any cheaper to build (or rent/sell) And the more you allow the more expensive it will be to build due to constrained supply of labor. Supply and demand - how does it work? lol

The cost aint coming down. And neither is the price as long as the capital required to pay for it demands a market return.

Source: based on my 30 years of experience as a housing developer.

I think everyone in the housing reform world understands acutely the cost issue and the limitations that currently exist, but most of the efforts on the supply side are to partly improve the economics of development by mitigating or removing regulations that basically exist to obstruct housing: inclusionary zoning (primarily), environmental review processes, “community impact fees” (ie, shakedowns), union labor requirements, etc. But absolutely, what is left unsaid is that the best case scenario is that housing prices simply increase at a slower rate and that incomes somehow need to rise.

-

2

2

-

1

1

-

-

13 minutes ago, Im_smarter_then_you said:

Ay-Eye. Nvidia + FAANG popping off over the last two years have the Peninsula real estate market back to record levels of stupid.

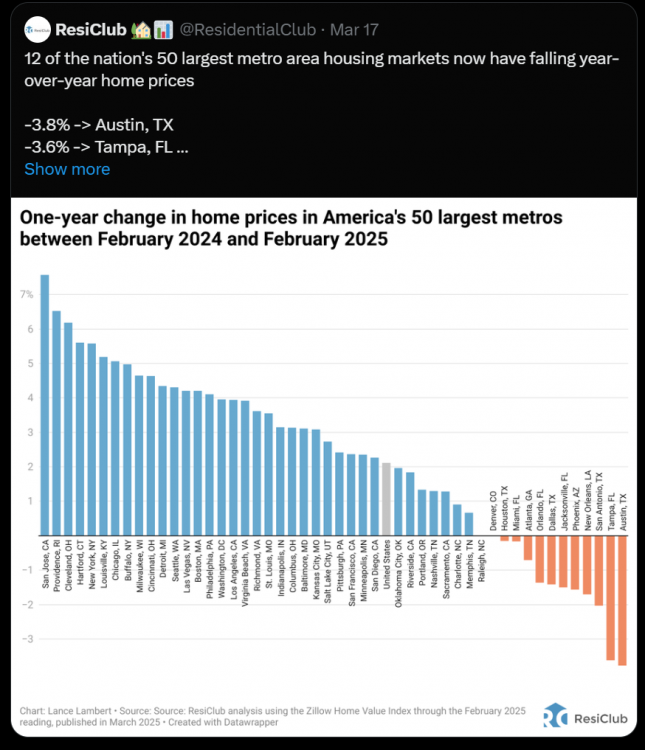

I also recommend “Abundance”, a big focus is why so many blue state cities are in the left column and red state cities are in the right column.

-

1

1

-

-

-

1 hour ago, Vegas64 said:

Had an awesome time galavanting around Nob Hill and Tenderloin. I did see a drug deal on Geary and Leavenworth though.

You get some Mensho?

-

11 minutes ago, BrickHorn said:

Trumpism is hedonism for assholes. It’s a license for callous shitheads to indulge their greediest, most inhumane impulses. So the idea that we should murder and/or displace an entire population of human beings, raze their homeland, and erect a tacky gilded monument to the Ugly American tourist on the ashes of this genocide couldn’t be more perfectly on brand.

-

3

3

-

-

24 minutes ago, CooterBrown said:

Some Russian Oligarchs are gonna want to get on the action here.-

3

3

-

-

5 hours ago, Napoleon said:

I didn’t know that.

Our biggest wine budget friend was in charge of the fantasy football draft location that year and his birthday fell on one of the days of our 4 days/3 nights.

His being a fairly successful investment banker based in Houston is a nice addition to the group of high school friends, but I guess that he covered more than just the accommodations that year (house with guest house and pool on 3 or so acres right outside of Healdsburg).

I had no idea that any of the 4 group tastings we did had cost anything. I just thought that if enough of our group purchased wine at the end of our tastings that the tastings were free.

Having wealthy friends has some privileges.

To be clear, no hate on Ceritas - prob one of my top 3 Sonoma producers. California winemakers are in a rough spot right now and they will do what they need to do make money. One easy way is to take advantage of wealthy Texas vacationers. Happy to provide perspective on wineries , but having lived here long enough to remember when these things were free, I balk at a lot of what I see these days.

-

1

1

-

-

5 hours ago, Napoleon said:

Best Chablis style Chardonnay in Sonoma County (that I have tried) came from the husband & wife team of Ceritas wines.

You may have to be on their email list to have access to their wine… and you may have to visit their winery to get on their list, but their various Chardonnays are fucking fantastic.

Light, slight fruit, medium+ acidity, some have a slight sur lie presence on some of their wines, but never beating you over the head with new American oak (the worst characteristic a white wine could have in my opinion)… just pure quality.

I just checked and their tastings are $95/pp in downtown Healdsburg? That’s absurd. Fuck it, go around the corner and get some Raveneau at Maison if you want to spend that much. Wineries are in a weird place right now but if I’m spending more than $30 for a tasting it’s going to be outdoors or part of some meal experience.

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

El Molino is awesome. Valley Swim is also nearby and another good easy lunch spot.

-

1

1

-

-

2 hours ago, Chopper said:

https://archive.ph/J20Cl no pw

Context of this issue is the County is trying to push for the state to streamline rebuilding like-for-like by exempting the county from the new state upzoning/development laws - in other words, a NIMBY push to prevent multi-family development.

-

49 minutes ago, Mo Horn said:

Anyone ever eaten at Lilette? Apparently Kelce and Swift ate there this week. Don't think I've seen it talked about here.

Yep, it’s a classic. Falls under the radar for tourists but it made the Pic’s Ten Best Restaurants for like a decade straight before they stopped the rankings.

-

1

1

-

Tequila y Mezcal

in Food and Travel

Posted · Edited by We’reTexas

Local shop (Tahona Mercado in San Francisco if ever in town).