Leaderboard

-

in all areas

- All areas

- Events

- Event Comments

- Articles

- Article Comments

- Articles

- Article Comments

- Articles

- Article Comments

- Articles

- Article Comments

- Articles

- Article Comments

- Articles

- Article Comments

- Articles

- Article Comments

- Sticky Posts

- Sticky Post Comments

- Commitments

- Commit Comments

- Files

- Topics

- Posts

- Status Updates

- Status Replies

-

Custom Date

-

All time

March 25 2018 - December 23 2025

-

Year

December 23 2024 - December 23 2025

-

Month

November 23 2025 - December 23 2025

-

Week

December 16 2025 - December 23 2025

-

Today

December 23 2025

-

Custom Date

09/05/22 - 09/05/22

-

All time

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 09/05/22 in all areas

-

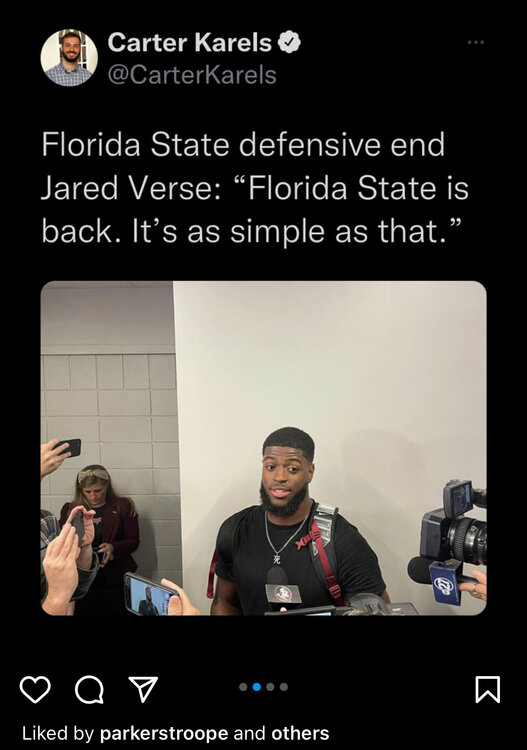

God, lift the curse that has been put on Texas football and place it on Florida State. Thanks30 points

-

29 points

-

20 points

-

As an outsider that roots y’all on, especially against OU, that’s where I’m at. I think the line is reflective of objective reasoning and the general public’s expectations, but I see a few opportunities…mostly rehashing old shit but I wanted to participate here: DKR will be an absolute madhouse, and yeah the ‘that’s every Saturday in the SEC bro’ folks may disagree but this is a once per generation event here in Austin. I’ve been there when it’s full tilt boogie time, and expect it to be 1.5x that at kick. Sark won’t be intimidated and has inside knowledge. If he doesn’t out-clever himself with a freshman QB and keeps the troops focused, the chess game should be fascinating. Hopefully he’s comfortable with risk taking on 4th/short, potential fake punts, baiting a flea flicker with Bijan, etc. Got nothing to lose and fortune favors the bold. Sanders. Huge advantage to have a flex TE like that with good hands that can play into all kinds of scenarios that offset their DL pressure. You’ve gotta mix him in unexpected places like a PA fake with Bijan or put him in as hybrid FB, and not just on 3rd down. Everyone knows they’re going to key on Bijan but your RB room is such an embarrassment of riches I hope to see some 21 personnel or diamond. Keep complex RPO plays out of your freshman QB but focus on getting the ball to proven players quickly outside of the box. Give the same basic look with a pop pass to Xavier or someone on a slant to put them in space. Defense has to have the ball bounce their way. ULM seemed to insist on running up the gut for 1-2yds a pop for half their plays though so not sure what was learned. Alabama will get theirs, so I guess your D needs to be Johnny on the spot for a lucky TO and otherwise tackle well to keep it manageable. Loved Overshown’s nose for the ball. Who knows about Ewers, my gut says that ‘settle in’ shit won’t work to start with Alabama like it did ULM. Theoretically you’ve got horses to stretch the field in both dimensions with RB, TE and WR…just hoping he can connect on a few bombs early on to make them adjust. Big time players make big time plays in big time games. Overall I’m jealous of the opportunity laid in front of you. Young players tend to let the moment get too big for them…but you’re at home, you’ve worked your whole career for this moment, and it’s time to lay it all on the table. Take it seriously as a measuring stick and maybe you surprise the nation. Rooting for y’all.19 points

-

18 points

-

I hope all of you pussies that tremble in fear at the mere thought of Bama are staying home Saturday. If you have them give your tickets to someone who is going to show up and cheer the team on with confidence. I don’t see this Bama team being that much better than last years version and they played plenty of close games and also lost to a bad A&M team. So fuck off with the, “we have no chance” takes. Y’all should be fucking embarrassed to even post such.18 points

-

17 points

-

We have folks on this board that will find something to bitch about if we beat Bama.16 points

-

It takes an incredible amount of arrogance, hubris and ignorance to be bothered by such a thing on behalf of the people who are appreciative and supportive of it. It sounds like you think the Seminole tribe are too backward to recognize how disrespectful and appropriative FSU's mascot and traditions are, so you have to enlighten them, or at least pity them from afar, given they lack the wherewithal to see what's really happening. Mascots are chosen for their inspirational quality, and everything FSU does, including the War Chant and tomahawk chop, are a celebration of that culture whose history is tied to that region. It's not cultural appropriation. Jesus Christ.16 points

-

16 points

-

16 points

-

14 points

-

This ain’t cultural appropriation and you look like a fucking clown. FSU and the Seminole Tribe are intertwined deeply. Stop insulting their culture you fucking dolt.14 points

-

14 points

-

Take notes? We don't need to take notes. This is our goddamned battleplan. There are a number of reports that the United States war-gamed this offensive with Ukraine, and used its findings to develop the current battleplan. And that's really pretty huge, because modern war games aren't like what we did in the 1960s (or even the 1990s), of a bunch of guys sitting around and doing moves and countermoves on a fancy chessboard. It's putting the variables into a computer and having AI run billions of simulations and finding the options with the highest rates of success. It's the kind of shit that Ukraine could never do on its own (and Russia sure as shit can't). And it reflects the degree to which our aid is far beyond a few HIMARS and M777s.13 points

-

12 points

-

12 points

-

11 points

-

They don't need some random internet Karen belittling them by deciding what they should be offended by...doesn't only apply to this scenario either11 points

-

Wordle 443 2/6 🟨🟨[emoji834][emoji834][emoji834] 🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩 I feel dirty11 points

-

11 points

-

You've got to think lucky. If you fall into a mudhole, check your back pocket - you might have caught a fish. ---- Darrell Royal11 points

-

10 points

-

10 points

-

I’m confused. She still has one unbroken wrist - right?10 points

-

10 points

-

You bring them because we’re going to beat Bama god dammit.10 points

-

10 points

-

10 points

-

Some of both, but tactical in my use. Germany had the RAF within days of becoming ineffective by hitting radar installations and airfields. A German bomber got off course and bombed a non-military target in London. The Brits responded with a raid on a German city with few military targets. The Germans then shifted the focus of their bombing from military targets to civilian targets, allowing the RAF some breathing room and a chance to recover. Germany lost their opportunity to defeat the RAF and invade England because of that change in targeting priorities.9 points

-

Actually, a certain level of incompetence (a lot of which is less practice time) really is part of what makes college football a more entertaining product. Just as an example, extra points were so automatic in the NFL that they moved them back and will probably move them back again. I mean it's great to see humans be that good at something that is incredibly difficult for most people, but it's boring as hell to watch.9 points

-

Calling out Chip for putting words in his mouth was pretty great. Lol9 points

-

9 points

-

The biggest difference that I see from Dems and Repubs with alleged crimes like with Hillary's server or Trump's document, is that Dems almost universally are ok if someone is punished if they're found to be guilty. Fine, sentence, whatever is appropriate. Republicans seem to immediately jump to their side is innocent or when the evidence is overwhelming, it ain't' that big of a crime.9 points

-

9 points

-

So the plan for next week is to be set up at 7AM or so. I’m going to the game and will bail around 1030 to get to the stands and get a drink etc. it is strongly encouraged for those who don’t have tickets to stay and watch at the tailgate. There will be a TV with an external Bluetooth speaker for extra volume. If someone has a 2nd TV feel free to bring it. The real party starts post game, so ditch your bullshit tailgate you go to instead of the surly horns tailgate and come over for at least a beer on your way out of the stadium - we will be showing all the CFB games the rest of the day, have a full service speed bartender, keg beer, and a full bar. I want to get “high end” food this time, open to suggestions I need to order catering soon for the game though. Plan on eating a post game meal around 330-4PM. I have a live DJ lined up as well. All donations will be going towards a 3rd BMF award - target goal of 10k. we will go until they kick us out.8 points

-

There’s a really good documentary on YouTube, will check my history and see if I can find it, about how the Germans had the RAF on the ropes. After the Brits retaliated, I think it was Hitler got pissed and wanted to lay waste to London. I want to say that the RAF was just a few days away from being rendered effectively useless, but I think it was definitely a week. Going after London (and other cities) allowed the RAF to get infrastructure/radar/etc. repaired, as well as building up a supply of aircraft. The Germans really had the RAF exhausted prior to the switch to cities.8 points

-

I enjoy FSU games because of their cool uniforms & colors, play anybody, anywhere history, and Chief Osceola & the War Chant. That right there is what CFB is all about. Go 'Noles8 points

-

8 points

-

8 points

-

8 points

-

That one is weird it's back and forth based on the player on offense with a lot of repeat plays. Here's the chronological condensed game Here's just the defense8 points

-

Did you take a picture of that phone with a different one instead of just taking a screenshot?8 points

-

How Justin Tucker Became the Greatest Kicker in N.F.L. History https://nyti.ms/3KvwhuN Nice write up by the NYT. The confidence, persistence, and all-out obsession required to play the least understood position on the field. By Wil S. Hylton Published Aug. 31, 2022Updated Sept. 1, 2022 Justin Tucker felt off. It was Sept. 26, 2021, and he was standing on the turf at Ford Field in Detroit for the third game of his 10th season as a place-kicker for the Baltimore Ravens. The game was almost over, and the Ravens had all but lost. Unless, with three seconds left on the clock, Tucker could boot the ball through the yellow uprights 66 yards downfield — a longer field goal than anyone had ever kicked in the N.F.L. The distance wasn’t a problem for Tucker. Or anyway, it shouldn’t have been. Tucker had kicked hundreds of balls farther than 66 yards. On game days, he began his warm-up by testing the strength of his leg in a series of increasingly long kicks. He never knew how far he could make it. Some days, he would blast it through from 75 yards. Others, he couldn’t break 70. But 66 was not, for Tucker, a lot of yards. “Typically, from 65, I’m able to get it there,” he says. Except this wasn’t a typical day. All through warm-ups, Tucker had been struggling for distance. One by one, every kick fell short of 65 yards. “I just didn’t feel quite right from the moment I got out on the field,” he says. “So when we’re looking at a 66-yard field goal, I knew I was going to have to just find something a little bit extra.” As Tucker jogged onto the field, he saw his snapper, Nick Moore, setting up at the line of scrimmage. His holder, Sam Koch, was seven yards back, where he would pin the ball for the kick. Tucker and Koch had been working together for a decade. They spoke a common language, but there was little to say now. Each knew that Tucker was having a weak day, and neither felt confident. They crouched briefly on the field, and Koch put a loose piece of turf back in place, then Tucker hopped on it with both feet to make sure the spot was flat. He tapped a toe to indicate exactly where he wanted the ball, then he started pacing away to prepare for the kick. Tucker knew he couldn’t rely on his usual field-goal technique. He and Koch had spent years practicing it to millimetric precision, but if it wasn’t going the distance in warm-up, he couldn’t risk it with the game on the line. To gain more power, he would have to make changes. He decided to make several. He would set up in a new position, jog to the ball at a different cadence and rotate his hip so far through the swing that he would have to land on the wrong foot. Tucker had no idea whether it would work, but he knew it was the best chance to win the game. He picked a new starting point and took a deep breath. Then he nodded for the snap and bolted forward, reaching the ball just as Koch pinned it to the ground. Tucker planted his left foot by the ball and bent his knee, leaning hard to the left as his right leg swooped down and his foot walloped the ball with everything he had. Usually, Tucker knew at the moment of impact whether a kick was good. This time, it was anyone’s guess. He watched along with the rest of the crowd as the ball soared downfield, dropping quickly as it approached the end zone. Then he saw it smack into the crossbar and shoot vertically into the air. Tucker heard the boink, but it was impossible to tell from midfield whether the ball had bounced back toward him or forward through the goal posts. Then he spotted a firefighter who worked for the Ravens standing at the end of the field. “I saw Avon go like this,” Tucker says, raising his arms to signal a good kick, “and it all kind of came together — first, like, ‘Holy [expletive], we won!’ and then, ‘We broke the record!’” Tucker streaked down the field as the stadium roared. His teammates hoisted him into the air, and broadcasters bellowed in disbelief. “Did that just happen?” the announcer Adam Archuleta cried on CBS. “I’ve never seen anything like it!” The kick would be played and replayed endlessly on sports channels and social media, with pundits declaring it “a thing of destiny” and “one of the greatest plays in N.F.L. history.” By the end of the season, it was still reverberating in recaps and highlight reels, and in February, the N.F.L. declared it the “Best Moment of the Year.” But in all the hype and celebration, something curious stood out: Almost no one seemed to realize that Tucker had changed his kick. You can pretty much always start an argument by declaring someone the greatest of all time, but the case for Tucker is becoming hard to dispute. One week after his 66-yard boink set the distance record, he broke another by making his 300th field goal in fewer games than anyone in history. Tucker also holds the N.F.L. record for accuracy. Since his rookie year in 2012, he has made 91.1 percent of his field-goal attempts, and over the past decade, he has scored an average of 136 points per year — which is more than any other player, in any position, ever. When the Ravens announced last month that Tucker’s contract would be extended through 2027, precisely no one was surprised that his $24 million deal was the largest ever given to a kicker. Even so, like any kicker, Tucker occupies an awkward position. Kicking is the most consequential and least understood aspect of the sport. Place-kickers often lead their teams in scoring — 49 of the 50 highest-scoring players in history have been kickers — and they tend to be called to the field in their teams’ most critical moments: trailing by a point or two, with seconds left on the clock and miles of green to go. Every fan in every city can remember some harrowing game when all was lost until their place-kicker trotted out. Yet even the most ardent fan rarely knows much about kicking itself. Something peculiar happens at the sports bar when a place-kicker takes the field: All the granular nit-picking and arcane hairsplitting over the performance of other players will suddenly dissolve in a childlike hush of please God let him make it. Partly, that’s because a kick happens so fast. Even on a 70-inch screen in slo-mo, the kicker is little more than a blur. But mostly, it’s because kicking has nothing in common with the rest of football. Sure, the beginning of a field-goal attempt resembles a normal play: Each team gathers at the line of scrimmage to lunge forward at the snap. But the crush of bodies almost never affects the kick itself. By the time the first lineman wraps a meaty paw around another, the ball is already sailing to the holder, and in the space of 1.3 seconds, it’s hurtling toward the uprights. For the kicker, those 1.3 seconds may as well be another game. Unlike a quarterback — reading the coverage, searching for targets, scrambling to avoid a Watt brother — the place-kicker has nothing to gain by watching the field. His job is not to anticipate the opposition or back up his teammates. It is to enter a kind of trance, as if he were the last man on earth, and perform a complex choreography of his own. Tucker at a practice in August. The exaggerated skipping motion of his follow-through was inspired by the place-kicker Stephen Gostkowski.Credit...Philip Montgomery for The New York Times The details of that choreography are specific to his body. He has spent the bulk of his adult life searching for ways to improve them: adjusting his angle of approach to the ball, tinkering with the timing of each step, perfecting the orientation of his plant foot and making fractional changes to the arc and trajectory of his swing. He has considered the effect of a three-degree increase in the rotation of his hip on the backswing. He has trained the joints of his leg to move in opposite directions simultaneously, so his thigh can begin its advance toward the ball while his knee is still drawing back. He has carefully calibrated the sequence of his proximal-to-distal movements to exploit the kinematic potential of his own proportions. None of this is unique to the football kicker. The biomechanical exactitude would be familiar to a dancer or figure skater, and the incongruous interlude of a field goal has echoes in other sports — like a penalty kick in soccer or a free throw in basketball. What’s odd is how little a field goal has in common with football. Penalty kicks and free throws, after all, highlight a fundamental skill of their game. A field goal flips the fundamentals of football on their head. It interrupts a throwing game to let everything ride on a kick. It replaces the elegance of a spiral pass with tumbling, end-over-end rotation. It turns the spectacle of 22 bodies competing in coordinated combat into an extraneous sideshow for one player’s solitary performance. That is to say, what’s remarkable is not only the kick itself but that it happens in the middle of a football game, with the outcome on the line and 17 million people watching in terrified anticipation — most of whom have no idea what the kicker is actually doing. Growing up in the Westlake suburbs of Austin, Texas, Tucker lived on a cul-de-sac at the bottom of a hill teeming with kids his age. On any given afternoon, they might race through the streets on bikes and scooters or throw together an impromptu ballgame on the massive lawn across the street. Even then, Tucker was consumed by an almost cartoonish need to win. That was clear from the age of 4, when his parents enrolled him in a youth soccer league. “I remember losing a game and just crying my eyes out — being so pissed off, and mad, and upset, and sad and devastated,” he says. “And I remember my mom and dad both having to console me, like: ‘Hey, man, it’s just a game! You guys are 4, it’s OK!’” But Tucker’s intensity kept growing. At 10, he was accepted by a competitive club team and began traveling for games. “I remember making the team and realizing, Man, these other kids are pretty good,” he says, “but I want to be the best!” Tucker practiced constantly. He was forever dribbling a ball through the house, battering the baseboards and smudging the walls as he raced from room to room. By the time he entered middle school, his obsessive focus was developing a sharp edge. “I was probably a jerk,” Tucker says, “chewing other kids out for lack of effort. There were two or three of us who really wanted to win, but I was the one who vocalized it — and not in the most positive way. I’d be crushing other kids, and then their parents would be like, to my parents, ‘Hey, you need to get that under control!’” As Tucker recalls this, he is neither self-conscious nor especially regretful. “I’m wired a certain way,” he says. But Tucker also went through a deeply traumatic experience that may have accelerated his ferocious drive in those years. One day in fifth grade, a teacher gathered his class to break the news that one of their classmates had been in a tragic accident. He was traveling with his mother and sister on a small plane that his stepfather was piloting. There were complications in landing, the teacher explained, and no one survived. Tucker burst into tears. The student was his best friend. He left the room and was followed by a teacher, who tried to comfort him until his mother arrived. Looking back, Tucker says he was lucky to be surrounded by family and friends. “I could always talk to somebody,” he says. “I could talk to my parents, I could talk to my sisters, I could talk to my teachers.” But mostly, he didn’t. “A lot of the processing I did at that point in time was on my own,” he says. “It was, you know. ...” His voice trails off. “I think I’ll just leave it at that.” Over the past decade, Tucker has scored an average of 136 points per year — which is more than any other player, in any position, ever.Credit...Philip Montgomery for The New York Times At least two changes in Tucker’s life seemed to emerge from the loss of his friend. One was his longtime fantasy of becoming a pilot. His mother’s father was an Air Force veteran who flew missions over Vietnam, and Tucker had been fascinated by his stories, and by aircraft in general, since the age of 7. There was a framed poster above his bed showing the cockpit of a 737, but the dream of flight would fade. The tragedy also gave Tucker a heightened sense of urgency. He was acutely, if prematurely, aware that life is fleeting and more determined than ever to make his own exceptional. “To have an existential crisis at 11 years old — and not now, at 32 — is kind of strange and serendipitous,” he says. Sign up for The New York Times Magazine Newsletter The best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week, including exclusive feature stories, photography, columns and more. Get it sent to your inbox. If Tucker’s amplified intensity was alien to his soccer teammates, it was the prevailing spirit of Texas football. Although he joined his first team at the comparatively doddering age of 13, he instantly felt at home in the punishing fraternal culture. “I loved how guys would be yelling at each other, and pissed off and fired up and excited and pumped, all at the same time,” he says. By the end of his first season, in eighth grade, Tucker was playing half a dozen positions — including kicker, at which he thrived. Tucker’s local high school, Westlake, happened to be one of the country’s premier football programs and a breeding ground for N.F.L. stars, including Drew Brees. Tucker made the varsity team in his sophomore year, playing alongside future pros like the quarterback Nick Foles, the tight end Kyle Adams and the linebacker Bryce Hager. Even so, Tucker stood out. By the fall of his junior year, he was being scouted by colleges, and in February, he accepted a scholarship to kick for the University of Texas. But Tucker couldn’t bear to wait through another year of high school, so he spent the summer taking classes at Austin Community College, earning enough credits to graduate a semester early and become a Longhorn in January. “I was like, I’m going to get there as quickly as I can,” he says. “The more I can do before the football season starts, the better chance I have to play on Week 1.” Tucker didn’t just play on Week 1. He was on the field for every game over the next four years. As a freshman, he kicked off 94 times, for an average distance of 64.5 yards. As a sophomore, he kicked off 99 times, averaging 62.3 yards, and he completed 43 punts with an average distance of more than 40 yards. Tucker finally got the chance to kick field goals as a junior, making 23 of 27 attempts. By the time he smacked a game-winning field goal against the team’s bitter rival, Texas A&M, in his senior year, it was starting to look as if a pro career was more likely than not. In early 2012, he declared for the N.F.L. draft and posted a video clip online that showed him making 10 consecutive field goals from multiple points on the field. At the end, he walked by the camera, saying only, “Pick me.” A few days before the draft, Tucker received a visit from Jerry Rosburg, the special-teams coordinator for the Ravens, who took him to breakfast and watched him practice for nearly an hour. By the time Rosburg left, it was clear that he was impressed, and Tucker knew that the team’s kicker, Billy Cundiff, was coming off a weak year. He had missed an easy field goal in the final seconds of the A.F.C. championship game, bringing the Ravens’ 2011 season to a sudden and bitter end. But Tucker also knew the odds of being drafted as a place-kicker were long. Only one had been selected the previous year, and none the year before. In the last week of April, he watched the agonizing ordeal of player selection. It was a good year for kickers: four were selected. Justin Tucker wasn’t one. A field-goal attempt can be broken down into about half a dozen parts. There’s the setup, when a kicker paces from the ball to a starting position a few yards back. There’s the approach, as he jogs toward it in two or three accelerating steps. There’s the plant, when he lands his nonkicking foot a few inches from the ball, and the backswing, when he draws his leg back with a bend at the knee before unloading into the kick. Finally, there’s the follow-through, as his foot continues past the ball. Each of these movements has its own set of customs and conventions, but none are obligatory, and most kicking coaches encourage players to experiment on their own. That’s because anybody who’s serious about kicking knows that nobody knows that much. At a basic geometric level, the shape of a football is weird. It can be formally described as a “prolate spheroid,” which is another way of saying that it looks like a regular ball getting sucked into a vacuum hose. Scientists have been studying the aerodynamics of spherical objects for centuries, but experiments on the American football are comparatively rare, and the scientific literature on tumbling footballs is basically a couple of dissertations and a handful of obscure papers. “The reason not many people have looked into it is because it’s a very hard problem,” says Timothy Gay, a professor of physics at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, whose book “Football Physics” touches on kicking. “The tumbling ball is much tougher to model than a spiral pass.” For one thing, by rotating end over end, the ball is constantly changing how much of its surface meets wind resistance. For another, rotation itself can affect a ball’s trajectory, which is how baseball pitchers use spin to throw a curveball. But calculating that “Magnus effect” is substantially more difficult on a misshapen ball, particularly if it’s not only tumbling but also wobbling side to side. In the absence of scholarly research, kickers conduct their own. Their focus is not the football, per se, but how subtle changes in a kick affect it. The average N.F.L. place-kicker may not be able to tell you exactly how many millimeters below the ball’s centerline is the best place to strike for distance, or precisely what angle his foot should be rising from the grass at the moment of impact, but setting aside the numerical values, of course he knows. He has made hundreds of kicks with thousands of variations to develop his kicking technique, adjusting dozens of details in each part of the process, and dozens more within those — how far away to set up, how quickly to take each step of the approach, how close to plant the nonkicking foot, how far back to cock the kicking leg. Once the kicker has found his method, consistency is crucial. The smallest shift in one movement will carry into the next, magnifying with each step until things go literally sideways. All of which is to say that being a place-kicker requires more than power and coordination. Obviously, it helps to have plenty of both, and Tucker always has. “He had that type of leg — you could see the leg speed, and how the ball came off his foot like an explosion,” says Doug Blevins, a kicking coach who worked with Tucker while he was in high school. But Blevins also trained several other great kickers — including Adam Vinatieri, David Akers and Olindo Mare — and what distinguished them was not just physical ability but a strange combination of opposing psychological traits. On one hand, a kicker needs extreme confidence. “He wants to be in that situation where it all depends on him,” Blevins says. “All great kickers bring a certain amount of arrogance to the table.” And yet to perfect a kick requires an almost inexhaustible reserve of humility and patience as they subject themselves to an endless barrage of punctilious criticism and microscopic correction. “If I had to point to one thing as most important,” Blevins says, “that’s it.” “He had that type of leg,” a kicking coach that worked with Tucker in High School says, “you could see the leg speed, and how the ball came off his foot like an explosion.”Credit...Philip Montgomery for The New York Times Looking back, Tucker understands why he wasn’t selected in the 2012 draft. Although he practiced tirelessly, the university had no dedicated kicking coach, and he had reached the limit of what he could teach himself. “I would have been maybe — and this is a big maybe — an 80 percent kicker in the N.F.L., which simply doesn’t cut it for a team with Super Bowl aspirations,” he says. But Tucker got another chance. Just minutes after the final pick in the draft, his cellphone rang. It was Jerry Rosburg, the Ravens coach who had come to see him work out. Rosburg hadn’t been able to persuade the team’s management to use a draft pick on a kicker, but he invited Tucker to attend their rookie camp as an unsigned free agent. If the other coaches saw what Rosburg had seen, there was a chance they would sign him. Tucker flew to Baltimore in May. On his first day, he kicked a 55-yard field goal that got the attention of everyone on the field. At the end of his second day, Rosburg called him into a meeting with the team’s kicking consultant, Randy Brown — who spent the next two and a half hours playing video of Tucker’s performance and pointing out everything he did wrong. “His evaluation was essentially that I was not consistent enough in my set up,” Tucker says. “I was at too wide of an angle at the top of my stance, and I was taking my steps with only my plant spot in mind — as opposed to giving the spot of the ball equal consideration.” As the meeting wound down, Tucker promised to follow Brown’s advice, but privately, it made him nervous to reconstruct his technique in the middle of training camp. “I asked them at the end of the meeting for a little grace while I’m trying to figure this out,” he says. “Like, can you guys bear with me tomorrow, and don’t get rid of me if the ball’s not coming off my foot exactly how I want it? And they essentially said, ‘Yeah ... but no.’” The next day Tucker returned to the field with a knot in his stomach, but he set up for his first kick as Brown suggested. “And the first ball comes off my foot like a rocket, and then the next one and the next,” he says. “I just felt like I had command over the ball, something every kicker chases.” Tucker made every kick that day. Over the next few days, he made kicks like he had only imagined. By the time he returned home, he wanted a position with the Ravens more than ever. They were one of the only N.F.L. teams with a designated kicking specialist, and he was eager to find out how much more Brown could teach him. For the next two weeks, Tucker waited to hear from the Ravens. He turned down offers to practice with two other teams. He knew it was a gamble, but he was determined to kick for Brown. Finally, the call arrived, and he was offered a spot on the Ravens’ preseason roster. That would allow him to participate in the four preseason games, but either he or Cundiff was likely to be cut when the season began and the roster tightened. Tucker accepted the offer and returned to Baltimore, making six of seven field goals that he attempted in those games, including two of 50 yards or more. At the end of the month, the team announced that Tucker, not Cundiff, was staying. Fans in Baltimore were stunned. In The Sun, the columnist Kevin Cowherd insisted that it was a mistake to “go into the new season with a rookie kicker,” questioning whether Tucker would be able to perform under pressure. “I have this image in my mind: Ravens vs. Pittsburgh Steelers,” he wrote. “National TV audience tuned in. Ravens line up for a field-goal attempt with the game on the line. Welcome to the N.F.L., Justin Tucker.” Tucker would make 90.9 percent of his field-goal attempts that year, including four against the Steelers; one that clinched the divisional round of the playoffs in double overtime against the Broncos; and two in the fourth quarter of the Super Bowl, which the Ravens won by three points. He also finished the season with a perfect record for extra points — a streak that would continue for the next five seasons, as Tucker rose to the top of the league. It’s easy to look back on that rise as if it were preordained, an inevitable result of incomparable but inexplicable talent. In fact, what has distinguished Tucker from his first day with the Ravens is a relentless effort to get better. He has kept tinkering with his technique, week after week and season after season, as if he were still a rookie gunning for a spot on the team. Most of that tinkering is nearly undetectable. Even legendary N.F.L. kickers are sometimes astonished by his consistency. “He’s the most in-rhythm kicker that I’ve ever seen,” says Stephen Gostkowski, a former place-kicker for the New England Patriots. “He’s got the muscle memory to do the same thing every time. The guy is just absolutely amazing.” Yet Tucker is also always searching for small ways to drive the ball a hair farther or straighter or more reliably down the middle. In a pinch, he will tear down and rebuild parts of his technique entirely. When he finished the 2015 season with a disappointing record on long-distance field goals, he stewed and simmered, then immersed himself in footage of Gostkowski, who seemed to be making them all. “Stephen was absolutely outperforming me,” he says, “and his style was unique at the time.” Most kickers try to slow down their leg after striking the ball to avoid being thrown off balance. Some allow their leg to maintain just enough speed to lift them slightly off the ground, so their plant foot briefly skims the grass before landing a couple inches forward. Gostkowski took that skipping motion to a level approaching satire — after striking the ball, his leg continued forward with such velocity that it launched his body into the air, forcing him to hop several feet downfield before he regained balance. In his warm-up for practice the next day, Tucker attempted his first kick in a half-joking imitation. “Running through the kick, just totally exaggerated,” he says. He watched the ball pop off his foot with shocking speed, rocketing toward the uprights and smashing into a camera pole positioned directly at the center. He made three more kicks the same way. All three hit the pole. “So the first attempt I had that day with the team present was a 64-yarder,” he says, “and I just applied this new technique, the Gostkowski technique, and I don’t think I’d ever hit a ball as far in my life.” In the coming season, Tucker would use the skipping technique for every kick, missing just one of 39 field goal attempts to end the year at the top of the league, with a field-goal percentage of 97.4 percent. Tucker has been skipping through his kicks ever since, but more important, so have countless other players at every level of the sport. A technique that even Tucker found comically eccentric has, in part through Tucker’s prominence, already become respectable. One kicking manual published last year, Eric Piccione’s “The Art of Kicking,” recommended “a Justin Tucker skip-through to ensure you’re getting downfield.” But if Tucker’s tinkering with technique has helped to change the sport, it has also given him a unique range of options on any given play. That’s what made his record-setting 66-yard field goal possible — not the innate strength of his leg or the meticulous method that he has developed for field goals. On a day when everything felt off and his usual technique wasn’t delivering distance, he could tinker some more and cobble together a new kick on the fly. It was, he says, a hybrid approach, with elements that he normally uses for a kickoff. “So I took an extra half a step back into my stance, and I took a little crow hop into the ball, and a combination of divine intervention, adrenaline, technique that we had practiced for more than a decade, all came together in that moment.” He said this on a blustery morning at the Ravens Training Facility a few weeks later, gazing through a bank of windows at the howling wind. Practice was about to begin, and he was eager to get outside. Tucker insists on testing his leg in all conditions: If the field is slick with ice and snow, or the sky is black with driving rain, he will drag his snapper and holder outside to see if they can beat the weather. Today, as he suited up in the locker room, a scrum of reporters was milling around. They circled from player to player, asking detailed questions and nodding intently at the usual insipid answers: ball down the field, 110 percent, one play at a time. Tucker stood by his locker at the far end of the room and watched the commotion as he strapped on the last of his gear. Practice would start in less than a minute, but the reporters showed no sign of leaving. Tucker waited a few minutes longer, then pulled out a four-foot length of PVC drain pipe that was stashed by his locker. He raised the end to his mouth and, with the embouchure of a trombonist, unleashed a deafening wail. The room fell silent, but only for a moment. When the chattering resumed, he blew the makeshift horn again, and then again a few seconds later. Tucker kept blowing the horn until the last reporter gave up and shuffled out. Then he returned the pipe to its hideaway and did what he has always done. Tucker got back to work. Wil S. Hylton is a contributing writer for the magazine. He last wrote for the magazine about masculinity and violence.8 points

-

Scipio Tex Postmortem Offense. The Texas offense only ran 58 plays, but still managed 52 points on the strength of two non-offensive touchdowns, minimal penalties and 6.6 yards per play. Texas left a lot in the tank. Bijan Robinson notched only three touches in the second half, Quinn Ewers ran a stripped down offense after two shaky opening throws and couldn't connect deep with Worthy, and most of the starters were phased out in the mid 3rd quarter. Steve Sarkisian pulled Ewers a little early in my view. I'd have preferred Ewers have one more 3rd quarter drive with the starters, particularly after a couple of Sanders throws where he started to show comfort, but Sark saw enough. Pummeling teams you should pummel is good. However...in my preseason preview, I pointed out that ULM was a really terrible football team. In fact, I wrote: Nonetheless, if Texas struggles too much with the Warhawks in their season opener, turn this preview into a fireplace log and take up another hobby. and Breaking down the Warhawks player by player is not a particularly useful exercise. This game will be determined more by Longhorn energy, focus, and effort than anything Louisiana-Monroe does. I echoed the same sentiments in my weekly preview. A lot of potential for egg on the face with that kind of talk, but I watched their film. It doesn't take many reels to understand bad athletes + head coach padding his retirement accounts. I'm still seeing a lot of "Yeah, yeah, but we won big so...IT'S HAPPENING!" Fan is short for fanatic after all. I get it. Telling folks to cool their jets never goes over well. That second point from my preseason preview does have some applicability. Texas did show energy, focus, and effort. That's a base expectation. That's doesn't earn a letter grade or an Attaboy. It's Pass/Fail. Texas Passed. On to the real season now. QB Quinn Ewers had a shaky start, but eventually got it together. On his first throw, he hung up a go route to Xavier Worthy that could have been picked by a better single high safety, then threw a nonsense interception on 3rd and 7 into coverage. On that second attempt, which was from empty set, he had a clean pocket and a wide open Jordan Whittington four yards past the sticks, but chose to leave the pocket and halve the field to make something happen. You'll hear the Longhorn play by play guy say he was flushed. He wasn't. Bad QB play. What should have been an easy 14 yard gain and a new set of downs became a turnover. Sark had a nice little chat with Quinn on the sideline and then pulled back the reins on the offense for the next three quarters, which is a correct gauge of where the freshman is right now. A lot of simplistic single reads, check downs and a staple RPO. He overthrew Worthy in the end zone twice and also threw behind Keilan Robinson on a swing pass. When he finally nailed the lead on a little swing pass to Bijan, Robinson did the rest for a 16 yard touchdown. That's stuff he'll see in the film room and understand that if he can just distribute cleanly on time, Texas has good enough athletes to make him look good. In the 3rd quarter, Ewers also had a couple of nice connections with Sanders. The first, a little flip out improv where he felt Sanders trailing him and flipped it to him while pretending to look downfield. The second, a veteran instinctive step up in the pocket to find a streaking Sanders between two defenders (3rd Q, 9:57 mark). Quinn threw that ball effortlessly and the zip on it from a pure arm throw is good stuff. His final stat line of 16 of 24 for 225 yards and two touchdowns with one pick is largely a tribute to YAC (190 of 249 passing yards were gained after the catch) and a couple of Sark set piece gimmes (see Sanders TD throw). Ewers in on a developmental trajectory and Sark will dial up the offense based on what he sees Ewers can handle. The freshman will grow in fits and starts and it won't be a straight line. Fortunately, Texas has some weapons and a very good play caller to help him along. Hudson Card got a lot of action in the second half. He was sacked twice. One of them suggesting that his internal clock is still too often a sundial. Sark adjusted to his QB and the protection he was getting from the #2 OL and Card was successful on a series of sprint and roll outs, completing 4 of 5 short passes. The QB position is limited right now. But not by physical constraints. It will be fascinating to see various facets of the O open up as Ewers gains confidence, experience, sees the field better and starts tossing it around like the natural thrower he is. RB Bijan touched the ball 13 times for 111 yards and two touchdowns. He looked very good. No reason to take tread off of his tire, even if he could put up 100 yards in the second half running against the ULM defense. Roschon, Brooks and Keilan combined for 12 carries for 73 yards and two rushing touchdowns while Blue handled closing time. The backs are what we think they are and frankly, our quarterbacks needed the work. In the two back set featuring Keilan and Bijan, I wouldn't exactly describe Keilan as a blocker (see 5:05 mark in Q1). More of a I-got-in-your-way-er. WR/TE Ja'Tavion Sanders had a coming out party, suggesting that my prediction that the Texas TE who had not yet caught a collegiate pass would be on All Big 12 teams by year end could come to fruition. Sanders looked good as a receiver (6-85-1) and above average-ish as a blocker. A dual description we haven't seen here in a while. Let's see how it plays out. Gunnar Helm got the TE #2 snaps and was fine in about a dozen snaps. The Texas receivers didn't put up numbers as the game flow, a couple of missed balls, and some of the constraints on the offense disallowed it, but I was pleased with the blocking effort I saw from Jordan Whittington and Casey Cain. Whittington earned his Lambo like he was trying to eventually play at Lambeau with some absolutely outstanding blocks. He's just stronger than the average corner or nickel across from him, particularly the 170 pound variety. Casey Cain even contributed a pancake on Bijan Robinson's touchdown run. Cain had the best play of the day as a pass catcher, breaking a tackle near the line of scrimmage and then sprinting for another 40+ yards of YAC. Right now, he's WR #3 over Milton. Worthy was quiet with 2 catches, but hopefully he and Ewers get on the same deep ball page soon. Savion Red intrigued me in very limited action. Moves easy for a thickly built 205 pound freshman. OL Kelvin Banks has special feet for a 18 year old big guy and you can tell he takes football seriously. I only imagine what he can be once he gets strong and 20 starts under his belt. He and Hayden Conner did a nice job passing off stunts and slants to each other, albeit against weak competition. Jake Majors was alright but he's no stronger now on the field than he was as a true freshman. 3rd year player. There's no shock at contact. Cole Hutson showed good aggression, though he did give up the primary pressure that flushed Ewers into a sack. Hutson did a good job of sealing defenders on double teams a couple of times. A lot of guards want to drive the defender, but that often allows disengagement. Blocking him off and turning him is more valuable and an easy visual cue for the RB. HEY, CUT HERE. You'll see a good example of that on the Jonothan Brooks TD. Christian Jones had some good run blocks and held up as a Big 12 average right tackle. He may be overplaying the inside move given his struggles there and gave up some pressure on a couple of pass rushes that he should have driven past the QB by five yards. He also surrendered a sack on Card while in a double team with Gunnar Helm. That's a weird deal that happens more often than you'd think as both blockers essentially get in each other's way and neither declares definitively who has inside/outside. All in all, this group looked decently cohesive and focused, but ULM lacks the athletes to test much outside of gross incompetence. Final ULM is a bad football team. Have I made that sufficiently clear? The Texas offense will improve as the year goes on and Sark left plenty in the playbook for future opponents. Nothing is static when a team is starting three freshmen at the most developmentally intensive positions in the game. Alabama looms, but it's a mirage as a measuring stick. How the offense performs and grows against UTSA, Texas Tech, West Virginia, Oklahoma will set the season's upside.8 points

-

Wordle 443 4/6 ⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜ ⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜ 🟨🟨⬜⬜⬜ 🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩 I did not enjoy this on multiple levels. Watch yourself, Wordle.8 points

-

Note the start time is 11:30 AM Bandera TX time on LHN, local Austin radio, and here: https://texassports.com/watch/?Live=493&type=Live Longhorns cruise past ULM in the season opener 52-10 Longhorns 1-0. Next up:7 points

Football ... Basketball ... Baseball ... Other Sports ... Futbol ... 🤫995🤫 ... Gambling ... Movies & TV ... Music ... Hobbies ... Lulz ... Food & Travel ... Daily Texan ... Business and Markets ... Cloak Room ... Help ... For Sale ... Board Discussion ... Subscribe!... Donate!... COOKIE MONSTER!